Teesta's Fury and the Ancient Lessons We Ignore

- Gautam

- Dec 31, 2023

- 7 min read

On the night of 3rd October 2023, people were awakened by the roars of the disastrous flood, and within minutes the highest dam of Sikkim, India, Chungthang dam, built for Rs 13000 + Crore which was operational since 2017 was washed away leaving the place unrecognizable.

Picture credit: Mr. Richard Shen/ Internet

40 + Lives were Lost, 77 missing,33 Bridges were Destroyed, 80% of aquatic life lost

Chungthang is located at an elevation of 1,700 meters above mean sea level and serves as the meeting point for the Lachen River, which originates from South Lhonak Lake, and the Lachung River. These two rivers combine to form the mighty Teesta River. The Chungthang dam was part of a big project called the Teesta Stage III Hydro Electric Project, generating 1,200 megawatts (MW) of power.

In November 2023, my good friend Dr. Biswajit De, founder of Wildroots in Guwahati, India (https://www.wildrootsindia.in/main/index.php), invited me to be an Education Mentor for the '2nd Youth Climate & Conservation Fellowship Program' supported by IUCN-CEC (https://www.iucn.org/our-union/commissions/commission-education-and-communication).

I shared my river ecology experience with students during our camp in Seijosa, Arunachal Pradesh. Exploring the topic of river ecology, human impacts, and my personal connection as a Bengali to the Teesta River, I dug deeper into what transpired at Chungthang. While conducting my research, I consulted Mr. Richard Shen, my go-to expert on the aquatic life of the Teesta River basin. This blog reflects on the thoughts that emerged during my studies and discussions with Richard.

What is GLOF?

Before delving into further details, it's essential to grasp the geological phenomenon known as GLOF, which stands for Glacial Lake Outburst Flood. In regions with mountainous terrain, such as Sikkim, GLOF occurs as a natural event. This phenomenon occurs when there is a sudden release of an excessive amount of water from a glacial lake. The overflow or breach of the glacial lake can lead to a rapid and potentially destructive flood downstream, impacting the surrounding environment and communities. Understanding GLOF is crucial for assessing and mitigating the potential risks associated with this phenomenon in mountainous regions.

What is a glacial-moraine-dammed lake?

A glacial moraine-dammed lake is a type of lake formed by the accumulation of sediments, rocks, and debris carried and deposited by a glacier. As a glacier moves, it picks up various materials such as rocks and soil. When the glacier melts or retreats, it leaves behind these materials in the form of a ridge called a moraine. In the case of a glacial moraine-dammed lake, the moraine acts as a natural dam, blocking the flow of water and creating a lake. These lakes may pose certain risks, especially if they are located in areas prone to glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs), where the dam can breach and release large volumes of water downstream. Understanding the characteristics and dynamics of these lakes is important for assessing potential hazards and managing the associated risks.

South Lhonak Lake

Situated in the far northwestern region of Sikkim, South Lhonak Lake stands as a glacial-moraine-dammed lake with a unique distinction. Positioned at an elevation of 5,200 meters (17,100 feet) above sea level, it is among the rapidly expanding lakes in the Sikkim Himalaya region. This lake, a product of the Lhonak glacier's melting, holds the distinction of being one of the 14 potentially hazardous lakes susceptible to Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs).

Continuously fed by water from ever-increasing glacial melting, the size of the lake had grown from 0.20 sq km in 1976 to about 1.35 sq km in 2019 and it was a disaster waiting to happen.

And on the night of October 3rd, 2023, the worst happened. The left bank of the lake collapsed and a massive volume of water coupled with rocks, boulders, and other debris came down from an altitude of 5,200 meters with great velocity, reaching the dam site in just over an hour.

The reservoir of the Chungthang Dam was full and within 10 minutes, the Chungthang dam gave way, and the water gushed downstream wreaking havoc in its path.

Are we ignoring what Indian mythology has taught us so long back?

(Pic credit: Internet)

Let’s pause here and take a step back to ancient Indian mythology, a significant story of the force of a river.

After years of worshipping, Lord Brahma agreed to release Ganga from his pot to purify the souls of Bhagirath's late brothers. However, Ganga's descent to Earth would be forceful, so Bhagirath had to implore Lord Shiva to contain her in his braids; otherwise, she would inundate the entire Earth. When Brahma released Ganga, she descended with tremendous force. Lord Shiva, with his hairlocks, intercepted her, preventing a single drop from touching the Earth. Shiva retained Ganga in his hair until her force subsided. Once calmed, he released a small portion of Ganga and commanded her to follow Bhagirath. This is how our mythology says our revered river Ganga was born.

(Taisong River flood plain, Seijosa, Arunachal Pradesh, Pic copyright Gautam Gupta)

We can observe the structured arrangement of rocks and sediments along a river's course, seen as a means of calming its force, which echoes the importance of respecting a river’s natural course as emphasized in Indian mythology. While revisiting the story of the birth of Ganga, I kind of found a resemblance between Lord Shiva’s braids and flood plains, which control the river’s force during extreme events, to slow it down.

Floodplains demands respect

(Pic credit: https://wwfeu.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/livingwithfloodswwfpolicybriefingfinal.pdf)

Floodplains play a crucial role in river ecosystems. These are gravel riverbeds which are vital to the local ecosystems and help them to adapt to climate change. While the hydrological floodplain is visible, the topographical floodplain's extensive geographical range often goes unnoticed.

South Lohnak GLOF and Dams on Teesta Basin

According to experts, although the Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) in Sikkim could be considered an ecological occurrence, the subsequent disaster and devastation were undeniably magnified manifold by the series of dams along the course of the Teesta (https://frontline.thehindu.com/environment/article67453490.ece).

If we intervene in these floodplains especially in the Himalayan mountains by building dams, there is bound to be a reaction. The Sikkim disaster highlights the inadequacy of our understanding of rivers and the potential danger of human intervention, especially in the mountains. The Chungthang dam blocked the flood water and led to a change in direction causing wider damage.

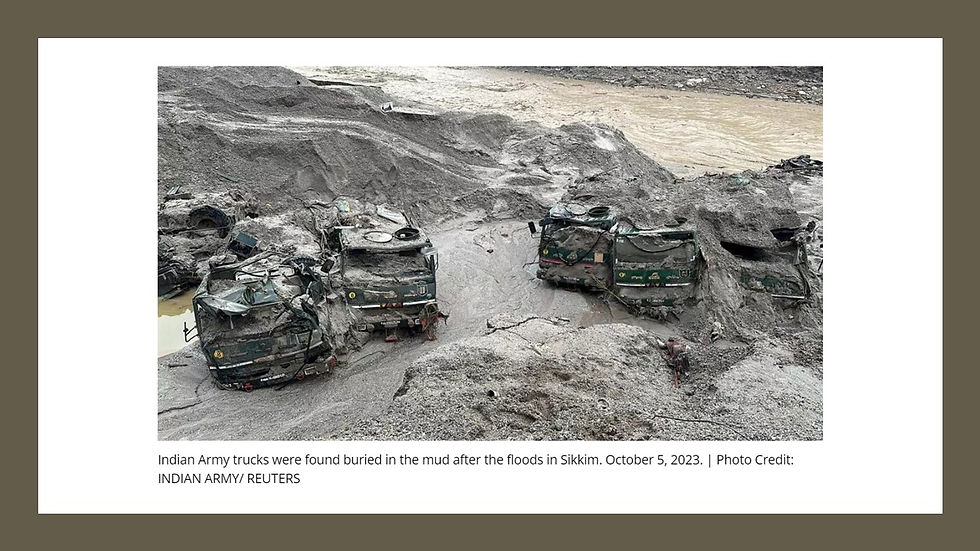

Dams alter the natural flow of rivers, affecting sediment transport and riverbed stability. This, in turn, can influence the severity of downstream flooding and landslides during extreme events. Local communities residing downstream are often at the receiving end of cascading disasters for no fault of theirs. At least 41 people have died in 27 villages across the four districts of Mangan, Gangtok, Pakyong and Namchi. 23 soldiers of Indian army were swept away from the barracks at Bardang, located 1 hour and 30 mins downstream of the flood.

While we humans have this tendency of evaluating damages in terms of loss to human capital, we normally tend to undermine losses to other plants and animals who are a part of the eco-system. My friend Mr. Richard Shen from Kalimpong was at the Riyang River to gauge the population of fish after the recent catastrophe. He found that the population has drastically declined - about 80% of the fish have been wiped out. You can read the detailed article here - https://www.sikkimproject.org/the-teesta-no-longer-flows.

It's high time that we learn our lessons from Mythology or other ecological disasters in our shortsighted attemps of controlling rivers

Is the Sikkim disaster of 2023 an abberatiion? Absolutley not.

The Vajont Dam disaster in Italy is one of the most infamous engineering tragedies in history. It occurred on October 9, 1963, when a a massive landslide, triggered by geological instability and heavy rainfall, fell into the reservoir. The displaced water generated an enormous wave, reaching up to 250 meters (820 feet) in height which completerly washed away many villages and the town of Longarone and 2000 lives were lost.

Speaking about Mother Ganga and her powers mention must be made of the Chamoli disaster, occurred on February 7, 2021, near the Nanda Devi National Park in the Garhwal Himalayas of Uttarakhand, India. Triggered by a substantial rock and ice avalanche from Ronti peak, the event led to widespread flooding in the Chamoli district, affecting the Rishiganga and Dhauliganga rivers, key tributaries of the Alaknanda—the major headstream of the Ganges. This disaster resulted in the loss of over 200 lives, predominantly workers at the Tapovan dam site.

The effect of Sikkim disaster would have been much larger had Chungthang or downstream of Teesta would have had a large town. But are we learning our lessons?

Experts are already raising concerns about two under construction, India assisted Hydroelectric Power Projects, Puna I and Puna II, at Bhutan (https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/the-shadow-from-the-fallen-sikkim-dam-falls-on-indias-hydroelectric-projects-in-bhutan/article67420574.ece)

I took this photo during my visit to Pakke Tiger reserver Sejosa, Arunachal Pradesh in the month of November 2023.

(Pic credit: Gautam Gupta)

If you look closely at the picture it looks like this rock face has been formed by rounded river rocks bound togther by some soil and sediment layer. The face looked extremely fragile held together by roots of trees.

Arunachal Pradesh is a part of young Himalayas, a place prone to seismic activities. I am no expert but then loosely bound rock faces like these are bound to crumble easily whenver a seismic event happens. So when I hear about mega Hydroelctric Power projects have been planned in the Subansiri and Dibang rivers in Aruncahal Pradesh, I get very concerned.

With our limited knowledge, if we persist in redirecting and interfering with the natural course of rivers to align with our interests, there are bound to be consequences. The disruption of a river’s natural flow greatly affects the river ecosystem and begins a cascade of reactions. Rivers has served as lifelines for civilizations and their diverse uses, from agriculture to industry. As human needs evolved, rivers were harnessed for hydroelectricity, creating an increasing demand for their exploitation.

Continuously building dams have led to the loss of many unique species which were critical to those regions. If the hydro electric projects in Arunachal progresses, it will destroy the rare and endangered fish species of those areas affecting the entire cycle in the ecosystem. While these consequences may not be immediately visible, their effects magnify over time and resurface in the future.

The recent disaster in Sikkim serves as a reminder that despite advancements in technology and knowledge, there is still so much to learn about nature’s complexities. The continuous construction of dams has led to the loss of unique species which are critical to the local environment. This is indicating that we need deeper understanding, respect for the natural course of river and we must acknowledge the interconnectedness of human activities with the environment to prevent such catastrophes and maintain stability in the ecosystem.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank the following individuals who have helped me in writing this blog.

Ms. Anushka Dutta - Student executive mentor, WildRoots and an aspiring plant scientist. Anushka is my co-author of the blog and helped me with necessary reserach

Mr. Richard Shen - Richard is an authority is the aquatic species of the Teesta river basin and works in tandem with ichthyologists and researchers from all over the country and abroad. He is associated with H.A.C.T an organisation out of Kalimpong to protect and save native fishes of the Eastern Himalayas.

One of the excellent articles , never heard, nor anyone has shared, should be released in the first page of every news paper. We as a common people can understand how important it is to do a proper risk assessment, but unfortunately, government is not going through, nor taking any expert advice before making long-term decisions. Resulting loss of human life.

Very well researched and beautifully penned, keep up the good work and keep spreading the word for a better tomorrow.